A Failing Sector in Need of Urgent Reform

- Connor Le'Gear

- Jul 18, 2025

- 3 min read

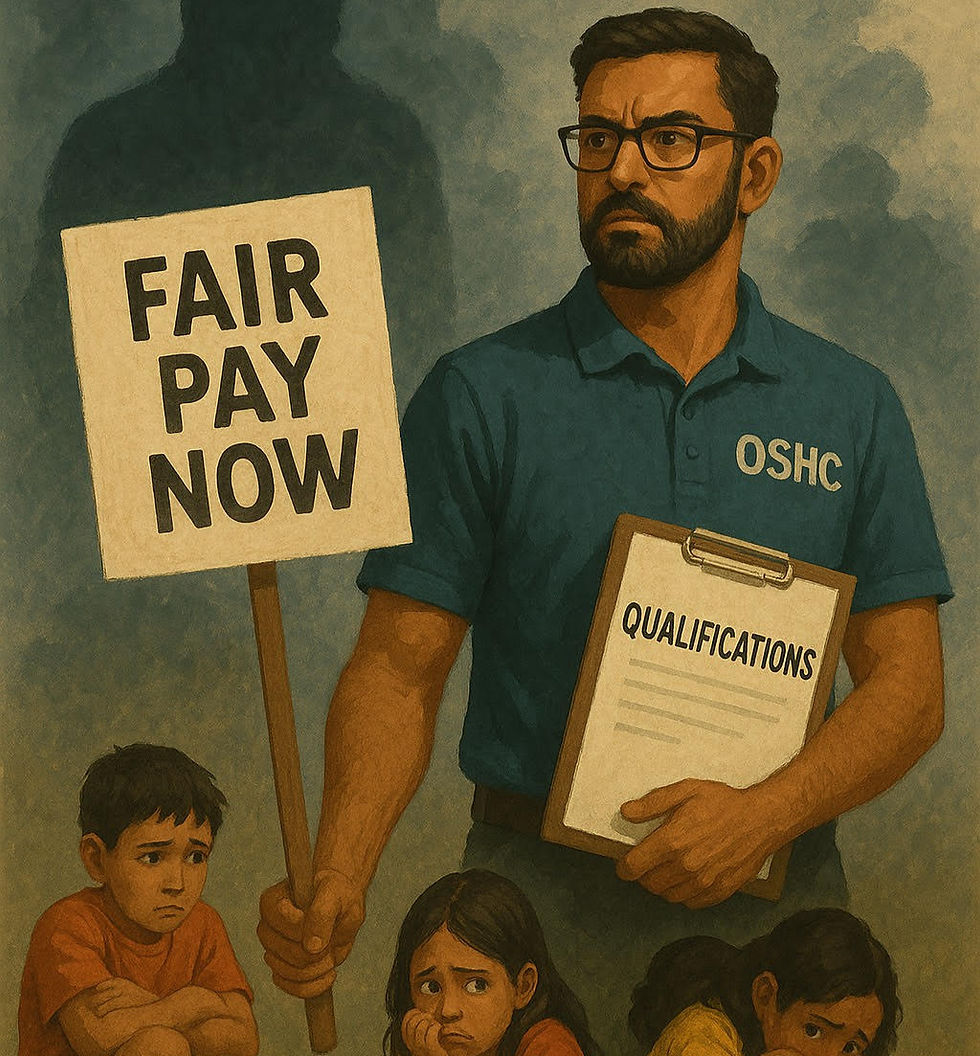

Australia’s Out of School Hours Care (OSHC) sector is facing a crisis. With growing reports of neglect, mismanagement, and even abuse, families are losing faith in a system meant to safeguard and enrich their children. At the heart of this crisis lies a conc

The bar for entry is too low, oversight is too thin, and the sector is woefully underfunded. To protect the wellbeing of children, we must urgently invest in educators—both through higher pay and stronger qualification standards.

OSHC services are supposed to provide a safe, stimulating environment for children before and after school. However, multiple reports and investigations have revealed serious lapses in duty of care, ranging from inadequate supervision to outright abuse. In many cases, these incidents occur because services are staffed by underqualified or poorly trained individuals who lack the skills—or, worse, the motivation—to work appropriately with children.

Currently, it's alarmingly easy to gain employment in an OSHC setting and in Childcare. In many states, minimal qualifications—sometimes just a working with children check—are sufficient to enter the workforce. There is little emphasis on early childhood education, trauma-informed practice, or behaviour management. As a result, children—particularly those with complex needs—are often left in the hands of staff who are not equipped to manage their development, emotions, or safety.

The sector's wages are a glaring issue. Many OSHC educators earn just above minimum wage, despite working irregular hours and bearing the immense responsibility of caring for children. This lack of financial incentive has created a revolving door of staff, with experienced workers leaving for more stable or better-paid roles. High turnover undermines continuity of care and prevents long-term bonds from forming between children and staff—bonds that are critical to emotional security and behavioural development.

When educators are overworked, undervalued, and underpaid, it creates the perfect storm for burnout. Burnt-out staff are more likely to make poor decisions, disengage from their duties, or treat children with frustration instead of compassion.

It’s time to change the narrative. We need to treat OSHC work with the respect and seriousness it deserves. That means introducing mandatory minimum qualifications—such as a Certificate IV or Diploma in School Age Education and Care—as a baseline for all educators. Ongoing professional development in behaviour management, child protection, and inclusive education should also be compulsory.

Crucially, pay must reflect this professionalisation. If we want qualified, passionate people to work in this space, we need to make it a viable career—not just a stepping stone. A meaningful pay rise for OSHC educators would not only attract higher-calibre applicants but also affirm that caring for children is valuable, skilled work.

Allowing the sector to continue as it is puts vulnerable children at risk. It sends a message that out-of-school care is babysitting—not education. But we know that what happens before and after school is just as critical as what happens in the classroom. These hours can provide opportunities for learning, social development, and emotional regulation—if the right people are in place to guide them.

Failing to act means continuing a cycle of neglect, and worse, abuse. The cost of inaction is children slipping through the cracks. The fix is clear: reform the workforce by investing in qualifications, professional standards, and fair wages.

Children deserve better. Educators deserve better. The future of the OSHC sector—and the wellbeing of thousands of children—depends on whether we have the courage to act now.

Comments